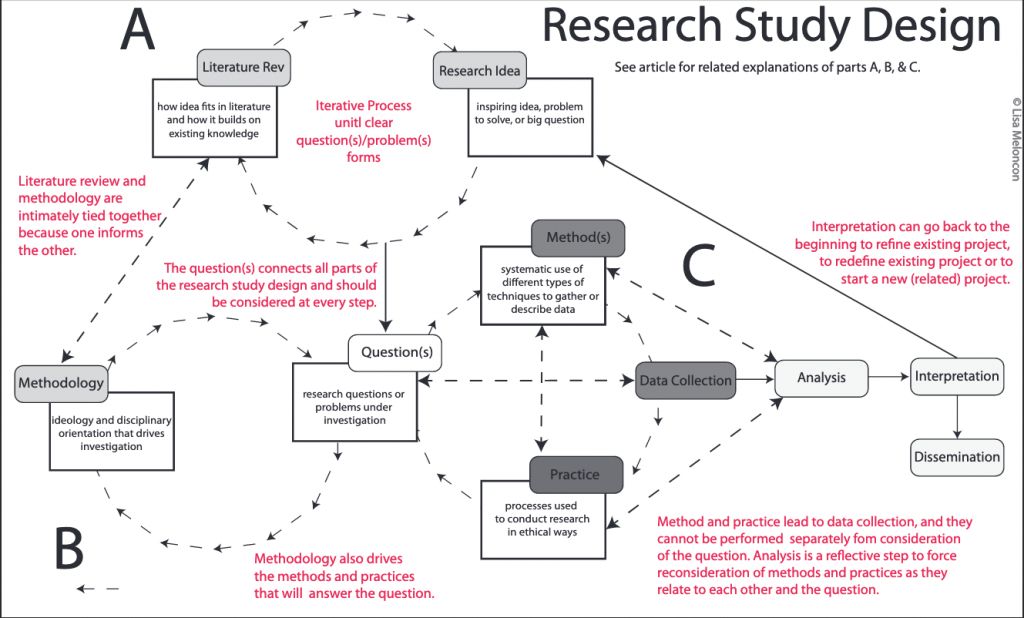

Literature reviews (often abbreviated in academic speak to lit review) shapes the study design. It’s done iteratively and simultaneously to the development of the question and closely with the choice of method(s).

When you go to write the literature review, it will help to show how your research question interacts with existing literature (or research). The lit review will also build your argument. You need to show how your study/project contributes to the existing scholarship. there has to be a connection that readers can see. A logical step through existing work to the main work of your own argument. Your research question(s) will shift, change, or be refined through this process. Remember that research is not linear and the relationship between question, lit review, and methods is an intimate one.

Types of Literature Reviews

If I had to sort of define the types of literature reviews found in academic research, I would make these big categories. :

- thematic: focuses on themes in the literature and how those themes related to your own argument

- chronological (or historical): walks through big moves through time or to show how things change over time (e.g., shifts in research from current traditional to process or how new materialism may have shifted from its first introduction to now)

- areas of similarity and dissent: hones in on the similarities and differences specific to your own argument

- limited: provides a clear indication that the engagement with literature is limited to very specific criteria

- theoretical: examines existing research in large part to show relationships between idea and to move to developing a new theory or approach or framework or [insert your favorite word here]

- comprehensive: incorporates a comprehensive view (that may follow one or several of the above) and shows this comprehensiveness to make a point related to your own argument (e.g., your lit review/theory chapter in your dissertation will be this)

These are just my way of helping you start to get your head around the approaches to writing a literature review. The mini definitions of these I provide are also ways to help you think about how the approach to the literature is directly connected to your research question and your methods. A literature review isn’t a summary of existing literature. It’s a deliberate and thoughtful approach to set up your own work and show what conversations are you talking to and with.

Note, these are the types of literature reviews that go into academic works such as journal articles or book chapters. At this moment, we are not concerned with literature reviews that can actually be peer-reviewed works themselves such as integrative literature reviews, systematic reviews, scoping reviews, or meta-synthesis reviews (to name just a few).##

Take a look at the this CFP from a few years ago: https://sites.uni.edu/grantd/CFP.html. CFPs’ are microcosms of entering conversations and situating the new idea/knowledge quickly and efficiently. Due to their length they are also (typically) mini-thematic lit reviews to help potential authors see how and where to situate their own ideas. While CFPs have a specific purpose, they can shed light on how to establish existing conversations and then situate your own ideas into them. You should be able to see how in a short space the main academic moves of a literature review are accomplished.

Moving to another example of literature reviews, let’s consider the dissertation. This weird genre has an expectation of the literature review being more comprehensive because the purpose of the dissertations literature review is to show you know things and have done the reading (both literally and figuratively). These literature reviews often appear in chronology to cover a lot of ground (both depth and breadth).

No matter the approach, the literature review has to situate and contextualize your own ideas.

Goals of your literature review

Keep three things in mind as you are gathering sources and writing the literature review:

Enter a conversation and build:rather than finding a gap, you are entering a conversation and building on existing work. That means, you have to start within the field in which you identify. Once you think have a handle on the literature related to your topic in your field, then and only then should you go outward to scholarship on the same topic in other fields. I provide information in this way because it is so easy with the inter-connected database world to gather a whole slew of scholarship that people in your immediate field may not recognize, this it undermines your own ethos as author. There are definitely moments when you should borrow and start outward, but in most cases, based on your projects you need to be working in the key journals in your primary fields and then move outward. If you do not know what those journals are, please ask, and or review the journal list.

Forward movement: Your literature review must say something by using the literature to set up your own argument by clearing indicating how you are building on existing work. Each piece (or series of pieces) needs to be one step toward the overarching goal of your literature review, which is to position your work and your idea in the conversation in a generative way (rather than saying here’s a gap I’m gonna fill). You can think of the lit review as the first phase on answering the two most important questions of research: what do I know? How do I know it? And most importantly, the literature review gives new insights into the “thing” by selecting the most key pieces to engage with, to show how the pieces fit together, and to illustrate a. new or different stance that is directly connected to YOUR work.

Clear language: The writing is what makes a literature review work so it is important that you spend some time on crafting the prose that helps connect the existing work and shows why this previous work is important to the field and to your argument. This starts by writing good summaries of each piece of literature (summary here means: key arguments, strengths/weaknesses of argument; key quotes)

Other sources on how to do a lit review

Some students find value in the following blogs in helps in understanding different parts of the research. YMMV (Your milage may vary). These are not gospel or things to the followed verbatim. They are resources to help you figure out your own way.

These are specifically on the literature review, but these three sites have other views on all the parts of the research process.

- from the political scientist Raul Pacheco-Vega (opens in a new window)

- from the thesis whisperer (opens in a new window)

- from education scholar Pat Thomson (opens in new window)

##The big tent of writing studies do few systematic, scoping, or meta synthesis reviews. TPC has moved to try to do more integrative lit reviews. This is why that one is the only one highlighted. If you are interested in pursuing this type of review for publication, I am happy to talk with you about what each does and how you may approach doing one.

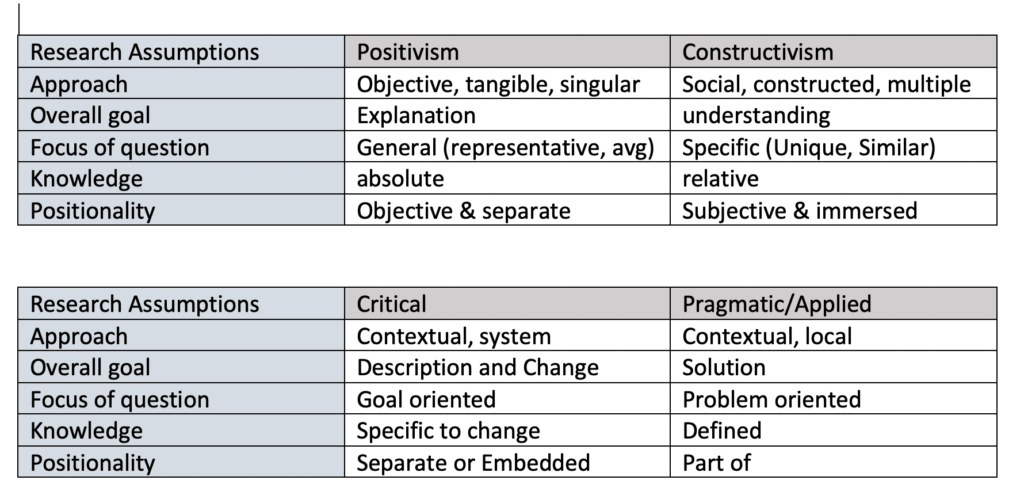

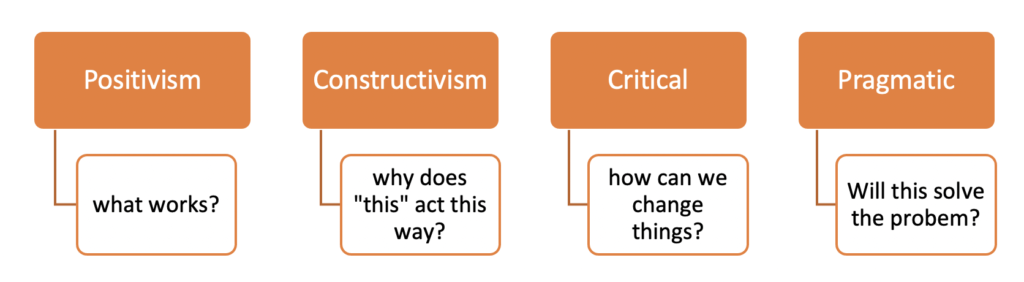

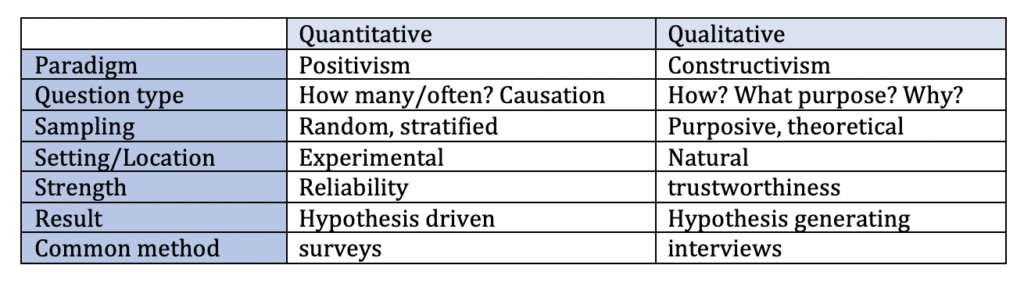

A research paradigm is “the set of common beliefs and agreements shared between scientists about how problems should be understood and addressed” (Kuhn, 1962). You should see an immediate problem with this ‘definition,” because it only points to research paradigms in relation to science. But it does and can apply to research in humanities and social scientists too. And Kuhn gets us started in thinking through how we want to orient ourselves paradigmatically in grounding how we approach the research enterprise or knowledge making. IN other words, a paradigm is where we can start and then move toward our methodology, methods, and practices.

A research paradigm is “the set of common beliefs and agreements shared between scientists about how problems should be understood and addressed” (Kuhn, 1962). You should see an immediate problem with this ‘definition,” because it only points to research paradigms in relation to science. But it does and can apply to research in humanities and social scientists too. And Kuhn gets us started in thinking through how we want to orient ourselves paradigmatically in grounding how we approach the research enterprise or knowledge making. IN other words, a paradigm is where we can start and then move toward our methodology, methods, and practices.