Research paradigms

A research paradigm is “the set of common beliefs and agreements shared between scientists about how problems should be understood and addressed” (Kuhn, 1962). You should see an immediate problem with this ‘definition,” because it only points to research paradigms in relation to science. But it does and can apply to research in humanities and social scientists too. And Kuhn gets us started in thinking through how we want to orient ourselves paradigmatically in grounding how we approach the research enterprise or knowledge making. IN other words, a paradigm is where we can start and then move toward our methodology, methods, and practices.

A research paradigm is “the set of common beliefs and agreements shared between scientists about how problems should be understood and addressed” (Kuhn, 1962). You should see an immediate problem with this ‘definition,” because it only points to research paradigms in relation to science. But it does and can apply to research in humanities and social scientists too. And Kuhn gets us started in thinking through how we want to orient ourselves paradigmatically in grounding how we approach the research enterprise or knowledge making. IN other words, a paradigm is where we can start and then move toward our methodology, methods, and practices.

Your “do for class” exercise should have led you to a large number of options and opportunities for understanding some driving ideas and terms the underscore all of research. So like last week when we generated some basic definitions of key terms, our goal this week is to also lay a foundation. Rather than purely definitional, we’re going to do some compare and contrast.

Ontology and Epistemology

These two terms are used a lot and in different ways.

“Methodology arises from epistemology, ontology, and axiology. How we know what we know, how we know what is true, and how we know what is good provide the tools for examining the world around us.” (Brock, 2020, p. 8).

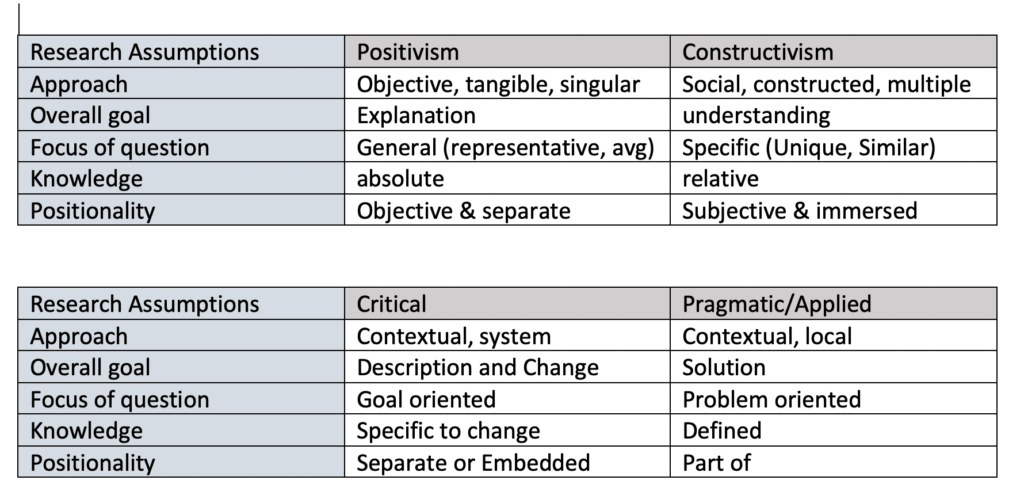

Paradigms and goals (sort of)

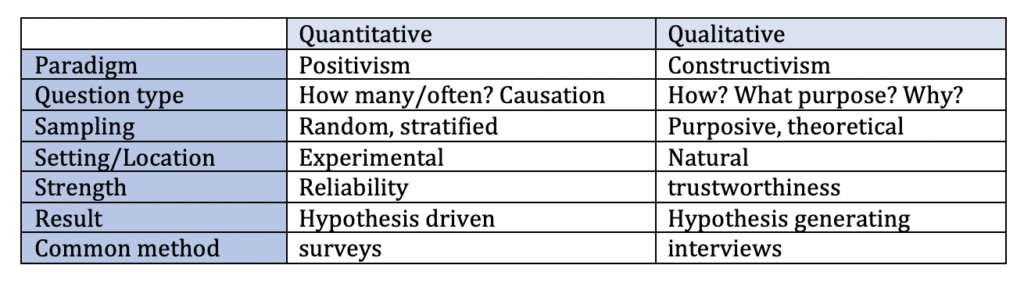

It’s important to remember that while I separated these for easier discussion that these paradigms are not in opposition to one another. These are not meant to be considered as one versus the other. Rather, it’s meant to visually show at a glance the common characteristics of the paradigms.

Now let’s think through the paradigms as relate to ontology and epistemology.

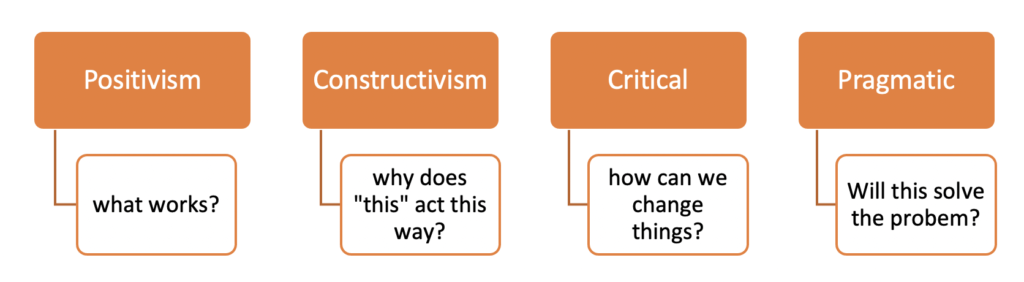

And then here are the types of questions they are trying to answer (in general)

Now take a moment to compare my little summary to the table on page 7 of this excerpt of a new book in technical and professional communication. I also link this here to show a field perspective that is within the larger tent of both communication and writing studies. In class, be certain to ask why we aren’t using this book as a primary text.

quantitive and qualitative

Often you will hear research broken into two big types of research: quantitative and qualitative. This distinction has been around for likely millennia, and I am not certain it’s a good distinction any longer. By that I mean, absolutely, there are differences in these two types of research but to try to focus so much on them (and their sibling mixed methods) often puts the emphasis on the wrong things, that is, we need to make sure we know why we are using a paradigm, an orientation, and a type.

Simply put,

- Quantitative—Numerical data that shows who, what, when, and where. Quantitative data shows scale.

- Qualitative—Data that demonstrates why and how. Qualitative data offers perspective and helps us understand not just what happened, but why and how it happened.

Mixed methods is when you design a research study that combine different types of methods. Originally, you would see the combination of quant and qual methods, but in the last generation of research (10 years or so), mixed methods also means a combination of methods even if they are all quant or all qual (e.g., a study using interviews, focus groups, and textual analysis).